At the same time, the risk of increased global trade protectionism continues. BMI Research predicts that trade giants — such as the US — will seek further restrictions in 2018, after a brief decline in such measures being implemented in 2017. The Trump administration has asked the US Department of Commerce to conduct studies into “unfair” trade practices, which could be used to justify tariffs. Meanwhile, succession risks dominate the political risk landscape in many African countries. And the threat of terrorism remains a concern, evidenced by attacks in Europe, Africa, Asia, and elsewhere in 2017.

The UK’s negotiations to exit the European Union continue to loom over the region’s political risk landscape. As talks continue, the risk that the UK will leave without a deal becomes greater, and companies may need to prepare for such an eventuality.

In Spain, political instability has persisted since August in Catalonia, as some there push for independence. On 21 December, regional pro-independence parties gained a majority in the Catalan parliament; however, bids for independence have not been recognised by Spain’s government, signalling that unrest in the region could persist.

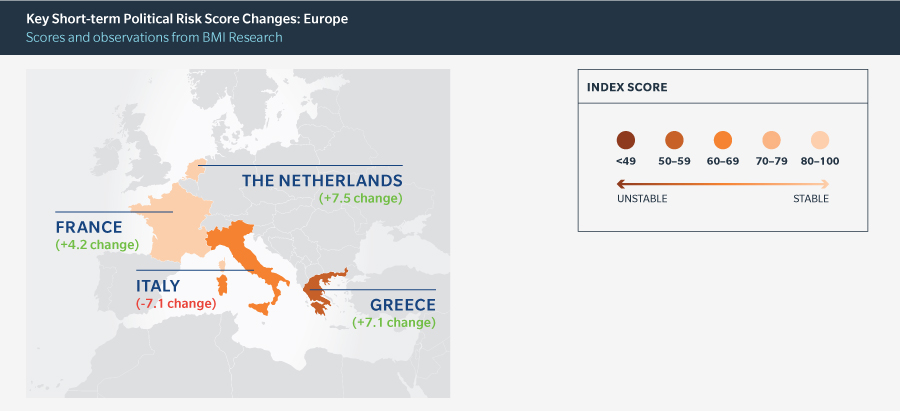

Terror attacks in Barcelona, London, Sweden, and elsewhere in Europe in 2017 have kept terrorism a major security concern. Elsewhere, the rise of far-right parties in 2017 created uncertainty around upcoming elections. General elections in Italy will take place in March 2018, raising concerns over whether anti-establishment and Eurosceptic parties, including the 5-Star Movement, will prevail. Current opinion polling suggests that the opposition centre-right bloc consisting of Forza Italia and Northern League (LN) looks set to emerge as the largest in parliament, but fall short of a majority. This could result in extended negotiations over coalition building, and the eventual formation of a weak government.

Nevertheless, Eurosceptic parties have recently backed away from calls for a referendum on Italy’s eurozone membership, and the robust macroeconomic backdrop in Europe should prevent market confidence towards Italy from declining. Greece experienced improvement in its political risk outlook, owing to greater policy stability and improved relations with its international creditors. BMI Research raised the STPRI for Greece from 52.5 to 59.6.

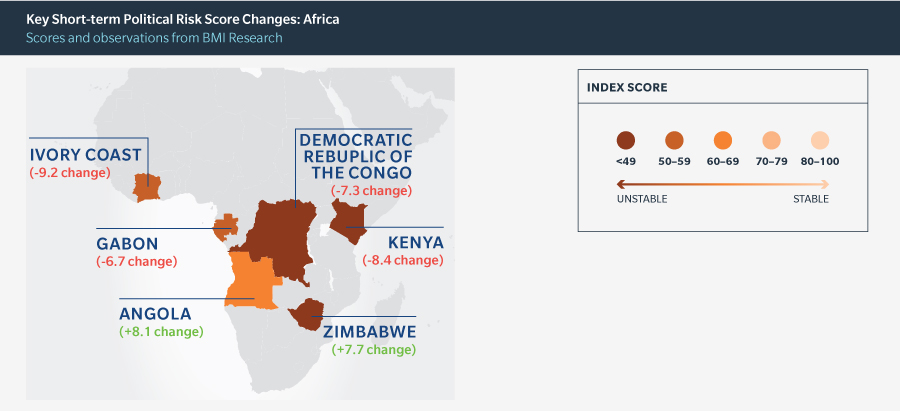

The African region once again saw some of the biggest improvements in political risk scores, but also some of the most notable deteriorations. Succession risks in Africa reached a decisive peak in 2017. In Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe resigned from power after 37 years, and the transition to Emmerson Mnangagwa appears to have gone smoothly, reducing the risk of political disruption in the country and improving its STPRI score from 37.7 to 45.4. Elsewhere, a smooth succession was seen in Angola, where longtime President José Eduardo dos Santos was replaced by João Lourenço in September 2017.

However, uncertainty around elections and successions led to sharp increases in political risk in several countries. Kenya and Gabon both recently experienced contested elections, and Cote d’Ivoire has seen political risk rise off the back of political jockeying to succeed President Alassane Outtara in 2020, while army mutinies continue in the country. Meanwhile, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) remains one of the most unstable countries, according to BMI Research. The country’s STPRI score fell further since the last update, from 32.7 to 25.4, as a result of uncertainty over when elections will be held, the weakening authority of President Joseph Kabila, and an increase in violence by armed groups.

The threat of Islamic State (IS) has somewhat subsided in the region in recent months, but conflicts remain. BMI Research raised Syria’s STPRI from 22.9 to 27.9 as President Assad’s government regained territory from rebels and IS is considered less of a threat. However, BMI Research noted that the threat of violence in Syria, as well as in Iraq, Bahrain, and Yemen, persists. At the same time, Qatar continues to face a diplomatic crisis, while tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran remained heightened. Other risks in the region stem from conflict between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon, between Israel and Hamas in Gaza, and more broadly, the risk of a new Palestinian uprising against Israel.

Tensions related to North Korea have dominated the region’s risk landscape over the past few months. BMI Research predicts the North Korean missile crisis will reach a decisive moment this year. North Korea has typically used important anniversaries to conduct missile tests, and BMI Research believes it will do so again this year.

In the East and South China Sea, tensions between China, South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam over disputed islands remain, but did not develop further in the latter half of 2017. China’s economy has experienced exponential growth over the past few years; however, this slowed in 2017, and it is uncertain whether it will pick up this year.

Multinational organisations face a complex and ever-changing political risk environment. Social instability and adverse government actions are among the most common examples of political risks that multinational organisations face when trading or investing in foreign countries.

Does this mean businesses should forego opportunities if they happen to be in potentially unstable areas? Not necessarily. While political risks are typically not directly controllable, in many instances they can be mitigated through credit and political risk insurance, providing greater confidence in the benefits of the opportunity.

Historically, multinational organisations have purchased political violence and/or terrorism insurance because the rates were typically lower than for political risk insurance. But companies should keep in mind that this strategy has the potential to leave significant gaps. Whether it is a political violence or a terrorism insurance policy that responds to a claim often depends on how insurers and governments view specific events. In some instances, terrorism and political violence insurers have denied coverage, claiming that a particular event should be covered under the other type of policy. Alternatively, political risk insurance can help bridge gaps by including coverage for both perils, potentially avoiding such disputes.

Trade contracts for the supply of goods and services with government or private entities in emerging countries are often exposed to a number of underlying political risks. Increased global protectionism, the restriction of hard currency payments to overseas companies, and the imposition of trade embargoes and sanctions are recurring issues in countries where governments attempt to enforce foreign policy objectives, influence domestic public opinion, or manage economic issues. Moreover, companies may find themselves faced with internal counterparty limit constraints that keep them from competing effectively in target markets. Contracts can be covered for terms of up to three to seven years or, if a buyer holds sovereign status, more than 10 years.

Drawing on data and insight from BMI Research, a leading source of independent political, macroeconomic, financial, and industry risk analysis, Marsh’s Political Risk Map 2018 presents a global view of the issues facing multinational organisations and investors. This interactive map rates countries on the basis of political and economic stability, giving insight into where risks may be most likely to emerge and issues to be aware of in each country.

Under BMI Research’s method, a country’s score is ranked out of 100 — the higher the index, the less political risk. This report considers the changes in the short-term political risk index (STPRI), a measure that takes into account a government’s ability to propose and implement policy, social stability, immediate threats to the government’s ability to rule, the risks of a coup, and more.

For more information on BMI research, visit their website: bmiresearch.com.

Below, we look at key developments in each region that are likely to affect the political risk landscape throughout 2018.

Since President Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, changes in US policy have been somewhat unpredictable. For 2018, this is expected to continue, and could include changes regarding global trade, with China potentially a key target.

The US mid-term congressional elections will be held in November for the Senate and House of Representatives, both of which currently have a Republican majority. A shift in power to the Democrats could create greater political gridlock. In addition, a war of words between Trump and North Korea leader Kim Jong-Un continues in 2018. North Korea’s recent tests of missiles, which are believed now to be able to reach the US, present a threat that could lead to US military action.

Several Latin American countries, including Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Paraguay, and Venezuela, will hold presidential and legislative elections in 2018. The uncertainty caused BMI Research to increase its estimate of political risk in each of those countries, as portrayed in the short-term political risk index (STPR), in which lower scores represent decreased stability. Venezuela has experienced continued unrest throughout 2017 as a result of an economic crisis, which has continued to weigh on its STPRI, now at 30.6. Suriname saw the steepest decline in STPRI score in the region, falling from 52.9 to 46.5, stemming from economic crisis and the ongoing murder trial of President Desi Bouterse.

DOWNLOAD AS A PDF